The last post described how an existing place name index created for the Rocque 1746 map had been georeferenced, and how the streets and notable places shown on the map had been digitised from the 1st/2nd edition OS maps of the early 19th century for reasons of their better spatial accuracy, and how digitised items were then processed to produce a set of polygons which accounted for each road and major place shown by Rocque. This posts describes the final operations where by those polygons were named, and how the parish and ward boundaries also captured by the project, were used to intersect or cut up those polygons such that there was a new polygon for every combination of ward x parish x street/place.

Naming the polygons

A simple two-point transformation had been used to place an existing index of place locations created for the Rocque map as graphics, into roughly their correct location on OS base mapping. In the central City area the articulation of a point and the polygon it represents, was good enough for the one to often be plotted inside the other. This means that any cases where a polygon did not have a point within it (or those which had more than one), had to be investigated. That investigation was manual but proved a valuable quality assurance ‘last pass’ of the dataset, with any points which were not quite in the right place would simply be dragged and dropped to correct them. A spatial join was then performed on the polygon enabling it to inherit the attributes of the point that fell within it – i.e. a place name.

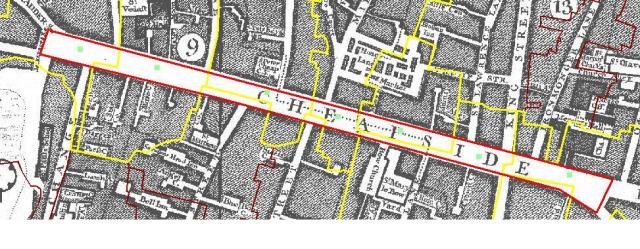

This then yielded a separate, named polygon for each street and place shown on the Rocque map. Now the job was to successively dissect those polygons using the parish and ward polygons as ‘cookie-cutters’ to punch out the newer smaller polygons. Returning to the example ofCheapside, we segmented the long thin polygon created for that thoroughfare, by cutting it with the parish layer, with the centre of each new polygon being automatically derived.

These operation had to be applied with some sensitivity, since ultimately we were not dealing with highly accurate datasets and some degree of spurious match of miss-match between data sets should be expected. For example when intersecting streets with the parish layer, we would find cases where a road edge and a parish boundary would have a slight miss-match, such that a sliver polygon would be created, implying that a tiny part of Street X lay in parish Y when in fact it never did. Filters were applied to ensure that minute, spurious polygons such as this could be omitted, but again they needed to be applied carefully, given the range of parish sizes within the study area. The following number of recorded were created (‘places’ includes streets and areas). Other challenging characteristics the data set exhibited included some parishes not being single polygons but rather comprised a number of discrete parts. Indeed a great deal of effort was expended on gathering a reliable set of parish and ward outlines in the first place.

Overall then the number of items dealt with were as follows

| Entity |

Number of distinct features |

| Places |

5,887 |

| Parishes |

191 |

| Wards |

99 |

| Places intersected with parishes |

7,121 |

| Places intersected with Wards |

6,711 |

| Places parishes and wards intersected |

7,847 |

| Parishes intersected with wards |

555 |

In summary then the project provided a number of observations, techniques and thereby opportunities to exploit other similar data sets. Chiefly perhaps;

- The need for detailed and informed graphical analysis, when creating composite images from historic maps which were only ever published as individual plates.

- The benefit of founding such an exercise on the firm base of the earliest reliable mapping one has of an area. By doing this the network, polygons and point data sets developed from one map of an area can be utilised for the creation of modified version of the same to service maps of an earlier or later time.

- The need for any such reference map base to extend beyond the spatial extent of the historic map being referenced. This is a manifestation of the surveyor’s adage – working from the whole to the part – whereby an external control network of accurate surveyed detail wholly encompasses the area of interest. The loss of accuracy over distance from the historic core witnessed in the warping effect seen on the geo-referenced Rocque map is simply a product of Rocque not following this maxim. That is he worked from the part to the whole, extending an accurately surveyed portion of the map out to the extremities within which he was not able to identify enough suitable targets to independently check accuracy.

- The great benefit of global geo-processing operations for improving the quality control of datasets, and automating complex tasks with the GIS. Many complex tasks were automated through the building of models or short programmes which would apply certain GIS tools in a sequence generating new datasets as they went.